AI, Commodities, and Why We’re (Still) Betting on Indonesia

2025 rewarded narrative stocks. We think 2026 and beyond will reward real earnings, real assets, and investors who are okay looking wrong for a while in order to be right for a decade.

Before we get into that, hi there! We help busy working adults with their long term investments in IDX with time tested value investing strategy. If you are curious, click here to find out more.

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. It’s a reflection of how we at Recompound currently think about the world. We can be wrong. Please do your own research or consult your advisor before making decisions.

2025: the year of narratives

If you only look at index levels, 2025 looks simple: “markets are at all-time highs.”

On the ground, it didn’t feel simple at all.

Early 2025 was full of pessimism, currency worries, and gloomy headlines.

By the second half of the year, the mood had flipped. Social media was full of green screenshots and questions from potential clients: “Should we be more aggressive? If not now, when?”

Under the surface, one type of stock dominated: narrative stocks.

By “narrative stocks” we mean businesses where:

the story and share price have already taken off,

but earnings (actual net profit) are still far behind.

We saw a similar movie in 2021 with digital banks. Prices went up 10–100x, the story was everywhere, earnings did not follow at the same pace, and eventually prices had to come back down.

2025 was generous to people who timed these waves perfectly.

We don’t think 2026 will be the same game.

We think the next phase will be kinder to something less glamorous but far more durable:

Earnings-based stocks – businesses where price still mostly follows profits, not just a narrative.

Especially in markets where the real economy is slowly recovering underneath the noise.

The AI revolution is real (and uneven)

Before we go deeper into AI, a quick bit of context on where we’re coming from.

Toby used to work as a software engineer at Goldman Sachs in Singapore, developing and maintaining mission-critical trading systems for the bank’s markets business. When your code breaks there, real money is at risk.

Budi used to work as a data scientist at GoTo Financial, building credit scoring models for their “Paylater” product. Machine learning models were literally his day job long before the current AI hype cycle.

So when we talk about AI, we’re coming at it as people who have actually shipped and maintained production systems—not just as AI tourists reading news headlines & watching podcasts.

And the simple reality is: the AI boom is no longer just a buzzword phase. You can already see it in the data.

In the chart above:

The red line is the S&P 500, steadily grinding to new highs.

The white line is total US job openings, which have rolled over and trended down since the launch of ChatGPT.

We’re not saying AI is the only driver of this divergence, but the pattern fits the story: corporate profits and index levels keep rising, while the demand for additional workers is flattening or falling.

That’s exactly what you’d expect if AI lets companies:

do more with the same number of people, or

do the same amount of work with fewer people.

In other words, AI is already showing up as a productivity boost for capital, not as a jobs boom for knowledge workers.

Who feels that pressure most? White collars !

Consultants and other professional services

Junior lawyers and paralegals

Auditors, analysts, and back-office knowledge workers

Software engineers whose work is mostly maintenance rather than system design

A lot of what used to require 100 knowledge workers can now be done by 10 very good people plus AI.

Who is less threatened in the next few years? Blue collars !

Construction workers

Miners

Technicians, field engineers and operators

Logistics, warehouse, and field staff

AI (LLMs) today mostly live in laptops, phones, and data centers — not in excavators and brick-laying robots.

And here is the twist that matters for us as investors:

AI is a great leveller for emerging markets.

A capable analyst or operator in Jakarta with access to AI tools can process information like a small team in New York and produce “global-tier” output—without Silicon Valley payroll.

So while AI is a direct threat to some white-collar jobs in rich countries, it is a productivity amplifier for capable people and companies in emerging markets.

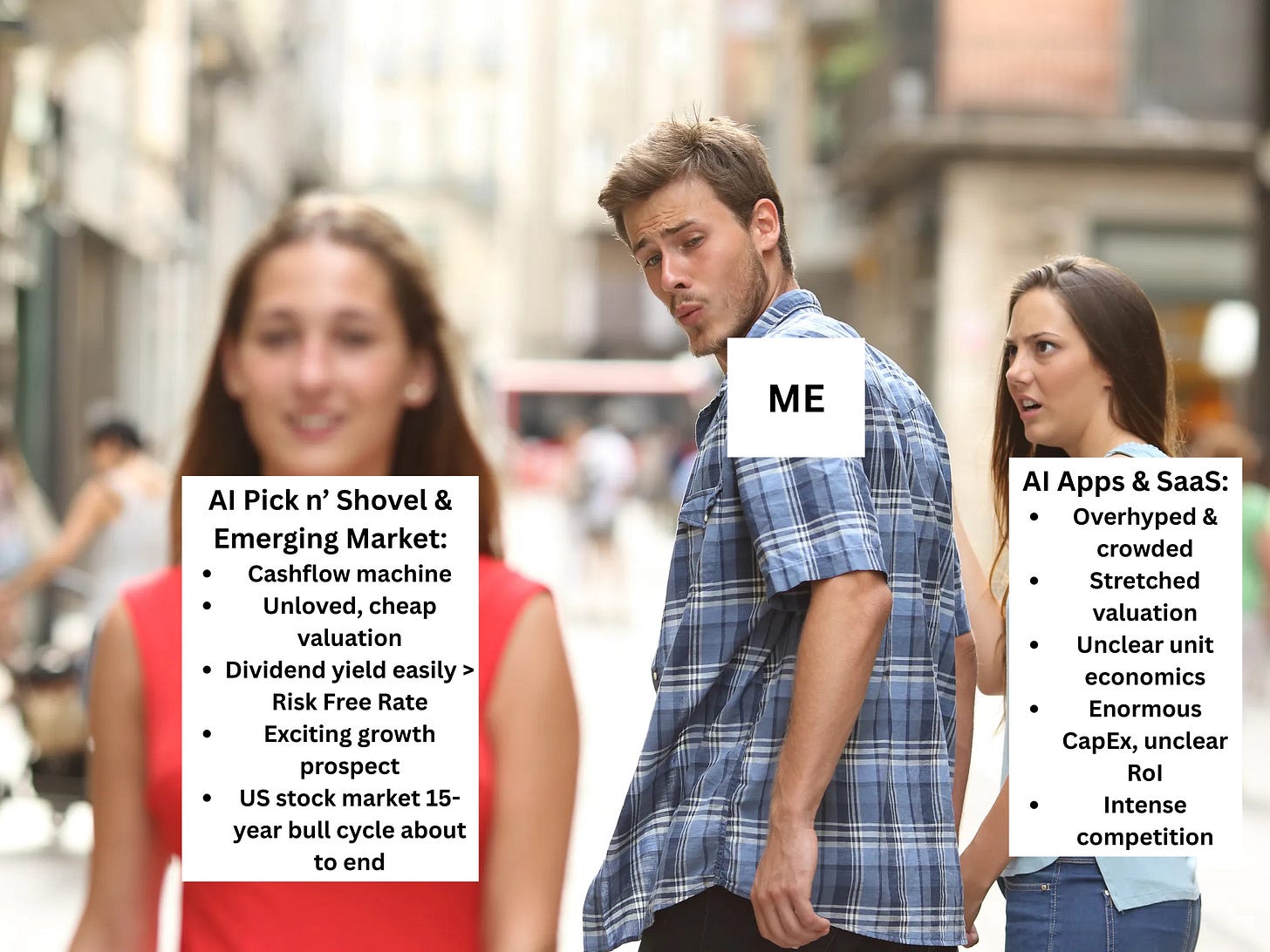

Why we are cautious on application-layer AI, AI SaaS, and (most of) the Magnificent 7

Before we get into that, hi there! We help busy working adults with their long term investments in IDX with time tested value investing strategy. If you are curious, click here to find out more.

If AI is so powerful, why aren’t we simply putting all our money into AI software, LLM platforms, and the Magnificent 7?

Because where you stand in the value chain matters.