Disclaimer: This post is for educational purposes and is not investment advice. Figures cited (e.g., P/E ratios) are point-in-time snapshots that change frequently. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Index data and third-party sources are believed reliable but not guaranteed.

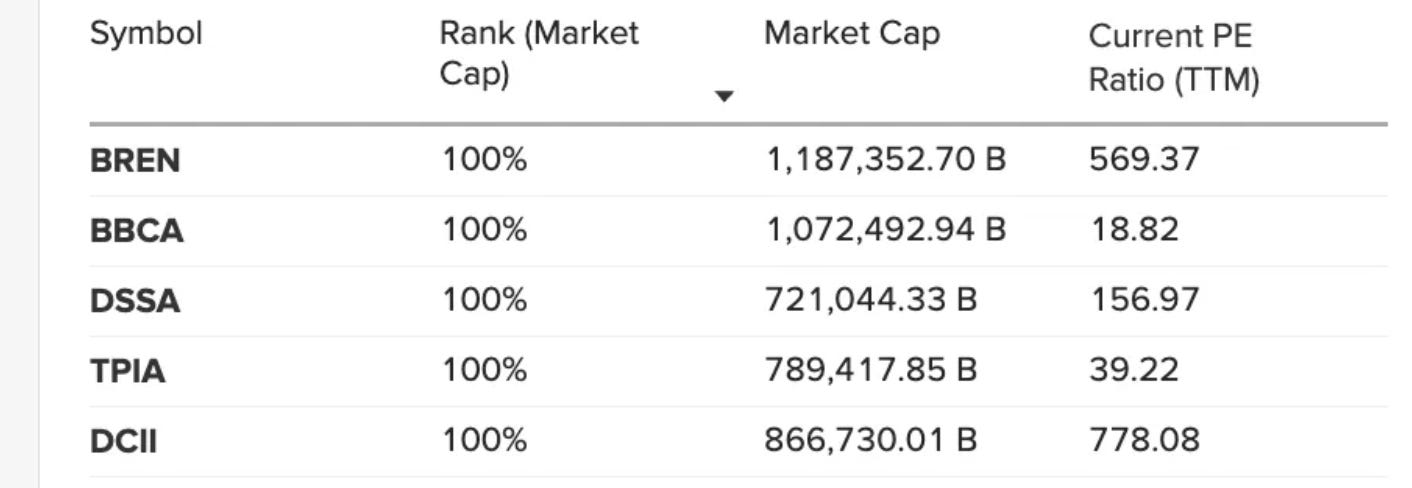

If you’ve watched our index IHSG lately, you’ve noticed something odd: a handful of stocks—often tied to conglomerate groups—have gone nearly vertical. Names like BREN, AMMN, DSSA, DCII have, at times, traded at triple-digit P/E ratios (some well north of 500x on trailing figures).

These moves don’t just make headlines; in a cap-weighted index like IHSG, they tilt the whole compass.

That’s why the IHSG can surge even while most stocks look like.. they are not going anywhere.

It isn’t a moral judgment though it is really just math. When a few very large, very fast-rising companies carry outsized market capitalization, they can distort how the IHSG looks, especially to newer investors who check only the headline index level.

Put simply, these stocks now drive IHSG:

“Is this only an Indonesia thing?”

No. The U.S. has been living a version of this, too.

At various points this year, the top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 made up ~40% of the entire index’s market cap—an all-time high. Concentration isn’t inherently evil, but it does mean the index can look better (or worse) than the “typical” stock underneath.

And if the whole spectacle feels familiar, it should: we saw a strikingly similar pattern during the dot-com bubble, which peaked in March 2000 before a brutal unwind.

What this means for Recompound (and for you)

Quick note: if you are new here you might want to find out what on earth is Recompound?

Over the past 10 months, Recompound has underperformed IHSG—largely because we haven’t chased the handful of names with extreme multiples. Over three years, our track record still outperforms the index. We know some newer clients (joined ≤1 year) are uneasy: “Why is my money lagging the index?”

Short answer: because the index has been temporarily dominated by a few stocks we don’t believe are priced for their earnings power. Chasing them might have juiced short-term performance—but at the expense of your risk. Our job is to compound capital for the long run, not to keep up with manias.

A short story about feeling wrong when you’re trying to be right

No investor captured this dilemma better than Jean-Marie Eveillard, the Paris-born fund manager who led what’s now the First Eagle Global Fund (formerly). In the late 1990s, as dot-com stocks screamed higher, Eveillard refused to play along.

Clients hated it.

“I’d rather lose half of our clients than half of our clients’ money.” — Jean-Marie Eveillard

They took him up on it. By multiple accounts, investors pulled a huge chunk of assets from his funds before the bubble burst—reporting ranges vary from about half to roughly two-thirds leaving. It was professionally miserable.

He once joked that value investing requires the courage to look wrong in the short term.

Then the bubble popped.

The scorecard: 3 years before vs after the peak

Using First Eagle’s own fact sheet for the Class A (SGENX) share class:

3 years before the peak

1997: +8.5% (MSCI World +15.8%)

1998: –0.3% (MSCI World +24.3%)

1999: +19.6% (MSCI World +24.9%)

(Painful relative years. Clients were restless & churned)

3 years after the peak

2000: +9.7% (MSCI World –13.2%)

2001: +10.2% (MSCI World –16.8%)

2002: +10.2% (MSCI World –19.9%)

(Held its ground while the benchmark fell hard.)

The discipline that looked foolish on the way up looked wise on the way down. In the early 2000s,

Eveillard was recognized with Morningstar’s International Stock Fund Manager of the Year (2001) and its inaugural Fund Manager Lifetime Achievement Award (2003).

Meanwhile, many funds that rode the dot-com wave imploded or faded into footnotes.

As just one emblematic case, the Munder NetNet Fund rocketed +176% in 1999, then fell –51% in 2000 and –46% in 2001; years later it was a fraction of its prior size.

Contemporary reports chronicled tech-focused funds shutting down en masse.

The other side of the lesson: even legends feel FOMO

Even the best can stumble. Stanley Druckenmiller—George Soros’s famed lieutenant at the Quantum Fund and the strategist behind the 1992 pound-sterling trade (the man who broke Bank of England) — knew the bubble was frothy.

He stayed disciplined…until he didn’t.

In his own words, near the top in March 2000 he “bought $6 billion of tech stocks” and, in six weeks, “lost $3 billion in that one play.”

He soon left Soros Fund Management as the firm restructured after steep tech losses.

Two takeaways:

Experience doesn’t immunize you against FOMO.

Process beats impulse. Druckenmiller himself has said he already knew better—he just didn’t act better in that moment.¹⁷

Back to IHSG, today

Multiple IHSG heavyweights have sported triple-digit trailing P/Es at points this year (examples below).

IHSG is free-float, cap-weighted with a 9% cap per name—helpful, but not a cure-all for concentration.

The U.S. is simultaneously grappling with extreme concentration at the top of the S&P 500.

The dot-com era shows how quickly leadership can reverse when valuation and cash-flow reality reassert themselves.

Examples of extreme multiples

BREN – recent TTM P/E readings in the 500x.

AMMN – at 60x .

DSSA – at 150x.

DCII – at 700x.

What we’re doing (and not doing)

We won’t buy narratives at 500x earnings. Price still matters.

We’ll own businesses, not tickers. Cash generation, balance-sheet strength, and durability drive long-term compounding.

We’ll accept tracking error when the index is a rocket ship. Eveillard’s experience—and, ironically, Druckenmiller’s—remind us that discipline is easiest to abandon when it’s most needed.

If you joined us ≤1 year ago, you may feel behind. That’s understandable. Our commitment is the same: protect downside, insist on margin of safety, and compound. Over three years, that approach has beaten IHSG for us; over one year, it hasn’t—because we refused to sprint after a handful of story stocks.

We know which side of that trade we’d rather be on when the music slows.

Final thoughts

The hardest part of investing is staying sane when the benchmark makes you feel foolish. Eveillard’s clients left him in droves; Druckenmiller let a moment of FOMO override a lifetime of discipline. The market is a voting machine in the short run and a weighing machine in the long run. Our promise is to keep weighing.

If you’d like to find out more about working with us, you can head over here.