Everyone who wants to pick up a new skill will start out as a novice. I have yet to see a person picking up chess for the first time and be at the levels of Magnus or Hikaru. I also have yet to see a person who picks up football for a couple of months and suddenly be as good as Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi. It seems obvious enough for us to know that developing a skill takes time and effort in the world of chess and football. In other words, we don’t have to be good at football and chess to know that we suck at those sports (yes chess is a mental sport 😉).

But I am not sure if the same can be said about investing.

It seems to me that overwhelmingly many people are eager to declare that they are a great investor, especially during bullish times. Or at the very least, it seems that many people believe that achieving 25% is an easy thing after they buy a really expensive “investment course” that promises them 1,000% returns. The best justification for what I have heard for buying these investment courses is the following.

So if I pay Rp 10 juta for the course, I just need to make back Rp 10 juta from ONE successful trade.

Then, the rest of the trades’ profits are essentially 100% mine.

P.s. If you commit to this logical fallacy, that’s okay. Virtually everybody who buys expensive courses have a justification of that nature. Otherwise they won’t pay an absurdly expensive course.

In case you do not see the fallacy, you are assuming that carrying out ONE successful trade that covers your tuition fee ensures that you would have successful subsequent trades. But the subsequent successful trades are NOT guaranteed to be successful at all. Heck, you might lose the initial Rp 10 juta you received from the first trade and your entire investing capital if you are not careful.

Let’s use an analogy. If Magnus were to sell you a chess course for a suuuper expensive price and he says that “you will play like me”, you probably would be enticed and buy it. When you take the $10,000 chess masterclass course, he will share with you his secrets in understanding the chess game better. But after you learn his secrets, you realise that your chess did get better. You probably would learn how to play good openings principles. But still, when you go against better players, your lack of experience will cause you to make unforced errors (blunders) and cause you to lose your subsequent games.

To me, it is a no brainer that after you take a Magnus Carlsen course, you are likely to still be way worse than him at chess. Only when you put in the effort and time to be like him, then your ability would get closer to him.

Well this explanation, very much applies to investing… At this age of open information and technology, I think it is common knowledge that investing is also a skill, that needs to be honed and developed. You can buy the course to learn the skill, but you unfortunately cannot buy the skill. You have to practice it.

Setting up a premise: Let’s get back to investing. What does it mean to underperform?

But what then is being bad at investing? I mean in chess, you are bad if you keep blundering and losing your games. In investing, you are bad if you keep underperforming. But what is underperforming? Especially if many do not count floating loss as a loss and count realised profits as profits. If that’s the case, then everybody is good at investing. Which then means that no one really is.

Furthermore, much of investing unfortunately is not transparent. You cannot demand a person’s investments track record and measure it down to the T. Especially when the quest of this article is to figure out your friends’ investment performance. Such financial data is often private and sensitive.

Therefore, let’s get to the basics and define underperformance. You underperform if:

You hold on to your losers too long. You sell your winners too early.

Why do we set this definition as baseline?

We set it based on established knowledge known as The Disposition Effect that is well documented in academia. The Disposition Effect states that individuals become risk-seeking in the domain of losses. And the become risk-averse in the domain of gains.

It is important to note that this behaviour feels most natural to people.

For example, when you start playing chess, what feels natural is to blunder (forget that a piece is not protected when you make a move). In investing, the most natural tendency is to hold on to your unrealised losses and to trim your profits too early. As a matter of fact, a skill refers to your ability to overcome this natural tendency. The better you get in the said field, the better you are in overcoming this natural tendency.

What happens to a person during a floating profit

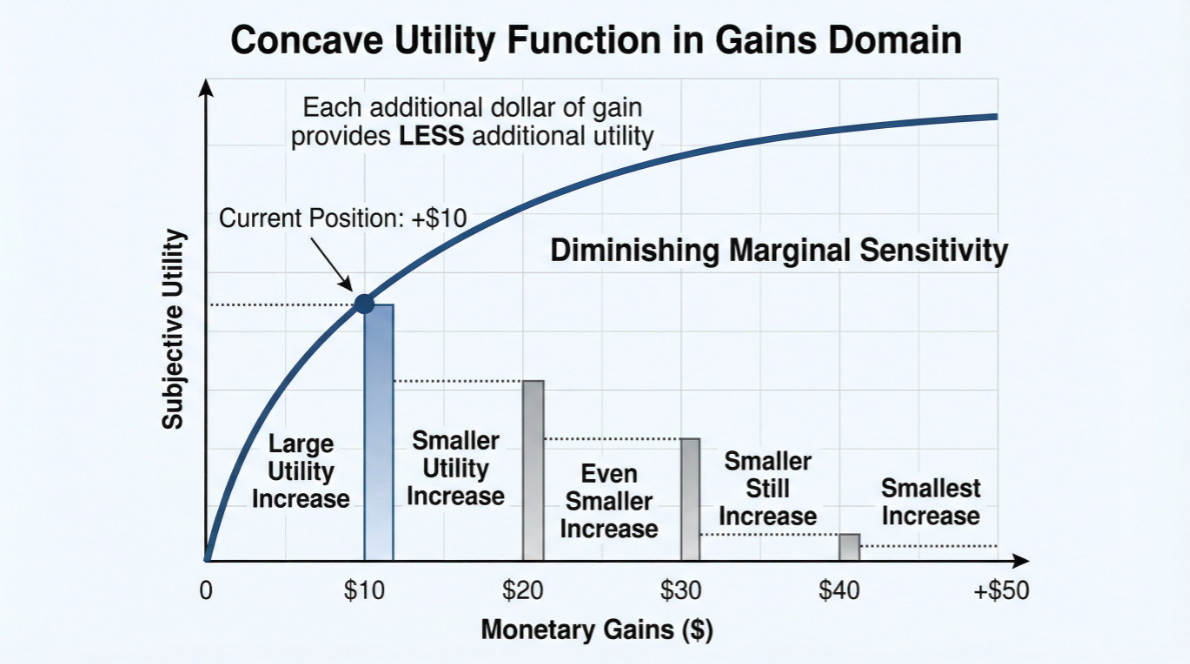

Research says Risk Aversion in Gains: In the domain of gains, the utility function is concave which causes investors to have the disposition to lock in profits early (selling winners) to secure the gain.

You can see from the figure above that the marginal utility for every $ gained, becomes smaller and smaller.

Imagine when you first bought a stock and that stock rallied 100%. That’s an awesome feeling. What Prospect Theory is saying is that:

From 0 → 100%, the gains feel hyper amazing.

From 100% → 200% feels amazing too, but less so compared to the initial 100% gain.

In other words, the 1st bagger might end up giving the same happy feeling as the next 200% leg up to your investments. Which is why, people tend to be more risk averse and tend to feel the urgency of taking of their profits early.

And what is the feeling that a person gets after realising their profits? Pride.

What happens to a person during a floating loss

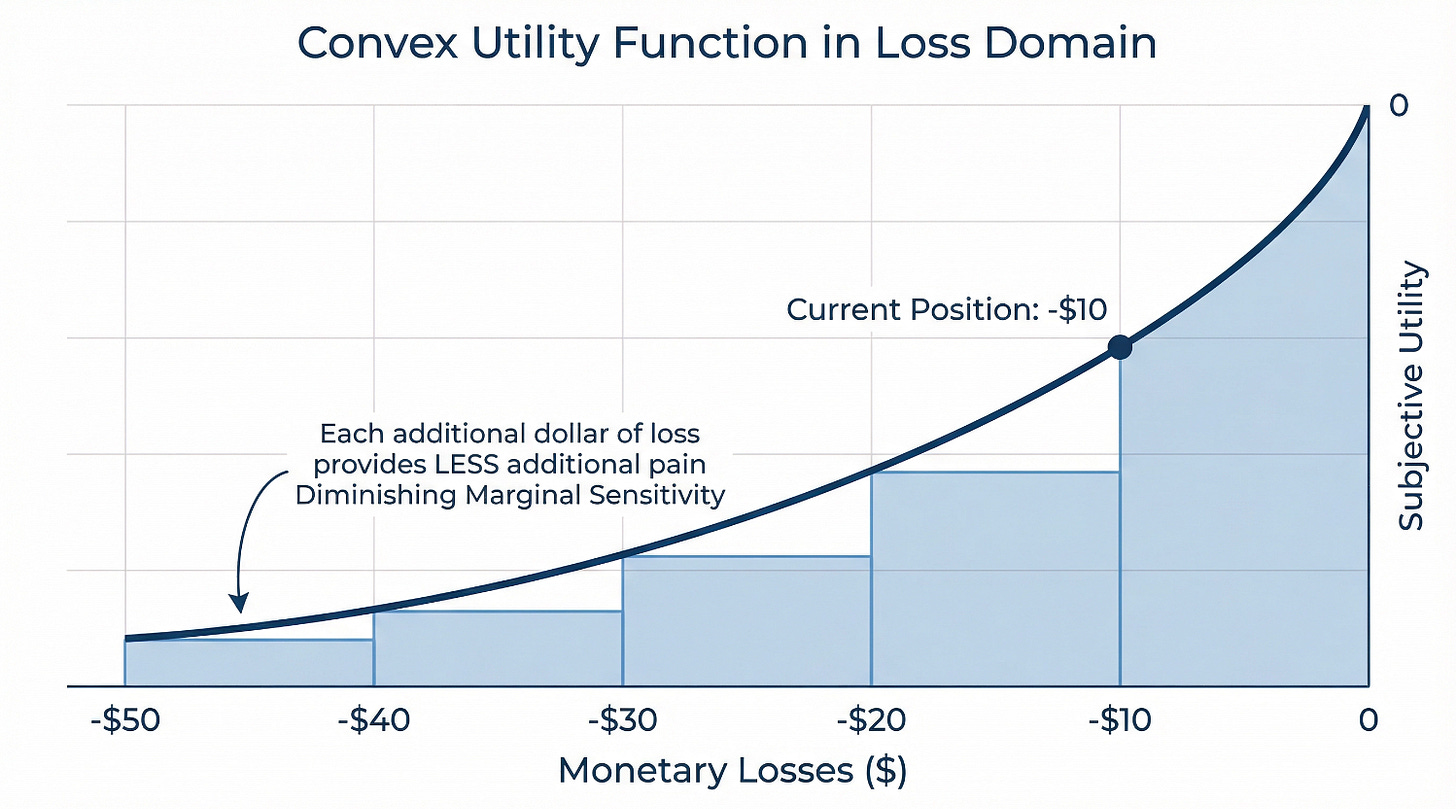

Research says in the domain of losses, the function becomes convex. This convexity implies that individuals become risk-seeking when faced with losses. Rather than accepting a “paper loss” by selling a declining asset, an investor prefers to hold the stock—effectively engaging in a gamble with 50-50 odds of breaking even or losing an additional amount

You can see from the figure above that the marginal sensitivity for loss of every $, becomes smaller and smaller.

So let’s say that you bought a stock and it goes down by 10%. It feels super terrible.

From 0 → -10% the loss is acute

But from -10% → -20% the loss is less acute and more numbing.

From -20% → -30% maybe it doesn’t feel anything anymore.

But that is why people have the natural tendency to ride their losses. Because the function is convex, if you are given the option:

100% chance you realise the -10% loss OR

50% chance you realise -20% loss and 50% chance you realise 0 loss

You will take the second option. Because 10% loss for certain feels more painful than the 50-50 chance of 20% loss and no loss. Although, the expected value is the same: -10%.

Intuitively speaking, people operate in wanting to minimize this very feeling of regret. Which is the negative counterpart of pride.

So What

So the natural tendency of an inexperienced investor is as follows:

In the case of profits, they want to seek pride as quickly as possible

In the case of losses, they want to proooloooongg regret as much as possible.

The more you conform to this natural tendency, the worse your investment performance. Also interestingly enough, when you conform to this natural tendency, your behaviour is often observable:

In coffee shops with your friends

In your office

In family reunions

Conjecture:

The way people converse about their investments reveal information about this behaviour and therefore, allows inference about their investment performance.

Note this is Toby theory. I have not seen an academic paper discussing this because I am not an academic. But I will be very happy to see if there’s a paper that discusses this more formally.

Hopefully this makes sense.

Again, the logic is simple:

Well-documented cognitive biases shape how investors react to gains and losses.

Those reactions lead to systematic underperformance.

And the same reactions show up in how people talk about their investments.

Which means:

by observing how someone talks about investing, you can often infer how well—or how poorly—they’re likely performing.

Without further ado, let’s go to the behaviours that allows you to infer your friends’ investment performance :)

Behaviour Symptom of Investment Underperformance #1: Boasting that one successful trade during family dinners or friends gathering

Pay attention to the way they boast it.

Do they simply quote a percentage gain?

Do they mention the size of the position relative to their total portfolio?

For example, if my dentist friend says:

“Hi Toby — I got 50% profit from stock A!”

I’d say congratulations. But I’d also form a reasonable belief that this investor is likely underperforming, for two reasons.

Number one, the are likely selling winners too early to secure pride. Boasting about gains is often less about returns and more about locking in pride.

As demonstrated in the previous section people’s natural tendency is to be more risk-averse in the domain of gains. Once a gain exists, the dominant impulse is not to maximize expected value, but to protect the emotional payoff of being right.

Essentially, selling early turns paper pride into realized pride.

This behaviour is observable because the investor highlights the gain before discussing its role in a long-term plan. The excitement isn’t really about compounding — it’s about getting validation from people around you. Which unfortunately in practice, this might mean:

Premature profit-taking

Truncated upside on the best ideas

A portfolio where winners never get the chance to meaningfully drive returns

Over time, this can systematically drag performance.

Number two, talking about stocks individually signals mental accounting. Notice what’s missing in the statement “my stock A is up 50%”:

There is no mention of position size, hence

there is also no mention of impact of stock gain to overall portfolio performance

The stock is being evaluated in isolation, not as part of a portfolio, which is consistent with mental accounting.

Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman describe mental accounting as the tendency for decision-makers to segregate gambles into separate mental accounts, rather than evaluating outcomes at the portfolio or total-wealth level.

When a stock is purchased, a new mental account is implicitly opened. Gains and losses are then tracked relative to the purchase price, creating a “scorecard” for that individual position.

So when an investor discusses stocks one-by-one — instead of contribution to total portfolio returns — they are verbally revealing this segmentation.

The problem is that:

Portfolios outperform, not individual stocks

If the size of the outperforming stocks is negligible to the overall size of the portfolio, then an investor should not be happy with merely a 50% increase. They should be demanding a 1,000% or a 10,000% increase for their investment bet. Hello Venture Capital.

Mental accounting breaks this integration, leading to sizing based on feelings, suboptimal profit taking times, and therefore poorer long-term outcomes.

Behaviour Symptom of Investment Underperformance #2: Getevenitis

Let’s say you are aware that your friend was super fired up about stock B and held it. Then you know that stock B plummets in value -50% since you last spoke with them. So you ask them with the intention to pique their take about the prospects of stock B

How’s your investments?

Then your friend would say:

Investment is fine. I’ll keep stock B for the time being. I believe it will go back up to my original buying price.

So essentially your friend is betting that stock B is going to double from this current price point. But hold on a sec, you can then ask your friend again:

What makes you think stock B is going to 2x from its current price?

If the answer is somewhere along the lines of:

I am not sure

My friend told me so

My broker told me to just keep it

Then we are seeing a behaviour that is often referred to as “get-even-itis” — a condition that has brought more destruction on investment portfolios than almost anything else. Logic as follows:

The original purchase price becomes a psychological anchor

Returning to that price feels like “undoing the mistake”

Selling below it feels like locking in failure

So instead of asking, “Is this the best use of my capital today?”, the investor asks, “Can I just get back to even in the unknown future?”

The tragedy is that positions don’t have to recover. They drift sideways, or worse, decline further — all while capital remains trapped. Although this sounds grim as it is not an ideal condition, we have written a systematic step by step to recover an investment portfolio.

But again, this psychological anchor and the reducing marginal pain of losing one more unit of investment, causes a risk seeking behavior. Essentially, you are willing to make an aggressive bet with your capital that stock B is going to double from today. Therefore, if you notice getevenitis, then you are likely having a conversation with an investor who’s underperforming.

Behaviour Symptom of Investment Underperformance #3: If only I knew this or that (Taugitumology)

Everyone can make predictions about the future. But everyone also doesn’t know what the future will be. Being an investor does not make you a soothsayer.

Being a good investor means that you can make calculated bets based on the information you have today about what the future is going to be. But it is impossible to be correct all the time. So if a conversation with your friend goes something like:

If only I knew Trump would strike Venezuela

If only I knew MSCI would reassess Indonesia’s free float visibility

If only I knew that silver price would go to $100

Well, what you’re hearing is not analysis. You’re hearing regret.

These are events that, by definition, could not have been known in advance without privileged access. And even if you somehow had an insider to Trump, you certainly wouldn’t have one to Xi Jinping — or every central bank, regulator, and commodity cartel in the world.

That’s simply how information works. Markets move not just on public data, but on decisions made behind closed doors.

What “if only I knew” actually signals

The phrase “if only I knew” is the verbal expression of regret aversion. Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman define regret as the emotional pain that comes from realizing, after the fact, that a different decision would have led to a better outcome.

The problem is not that regret exists — everyone feels it. Yes, including me and Budi. I happen to sell my silver stack at a $38. Does regret come about? Yes, very much so. Buut the problem is over-attachment to it.

When an investor constantly evaluates outcomes in hindsight, two things usually follow:

Decisions become ex post, not ex ante

Instead of asking, “Was this a good bet given the information at the time?”, they ask, “Why didn’t I predict the outcome?”

Process gets replaced by storytelling

The portfolio is no longer governed by allocation rules, probabilities, or expected returns — but by emotionally charged narratives about missed events.

This is why “if only I knew” is often a sign that the investor does not have a clear investment process.

Which repeated overtime, would most likely cause underperformance. I have yet to see the very few lucky individuals who don’t have an investment process and can generate a stellar long term investment performance.

Ultimately, 99.9% of people are playing status games

Being seen as good at a skill that is associated with intelligence feels incredibly satisfying.

We admire people who are good at chess because chess is perceived as a proxy for intelligence. The admiration is immediate. Think about the legends of chess like Gary Kasparov, Magnus, Hikaru. You won’t think that they are not intelligent.

Well investing sits in the same category.

If you are perceived as “good at investing,” the reward is instant:

Admiration and validation of your intelligence.

And if you happen to guess correctly, the feedback is fast. People notice. They listen. They ask questions. Which becomes a quiet boost to your social status. You are seen as the intelligent one in the dinner table with plenty of opinion.

The irony

I believe that the behaviours that maximize short-term validation seem to be the same behaviours that has the potential to destroy long-term performance.

As a society, we are trained to reward displays of intelligence. So investors naturally gravitate toward:

boasting about a single winning stock,

highlighting recent gains,

referencing dramatic events they “almost predicted.”

These make for good stories, but not a good sign for portfolio performance. Ironically, the investors who talk the most about being right are often signaling:

pride-seeking over compounding,

hindsight over process,

emotion over discipline.

In other words, the conversation itself becomes a diagnostic tool of some sort.

Closing Remarks

All this, I am definitely not saying that the person who exhibits this behaviour is stupid. It means they are human. I exhibit these behaviours too. I myself have my own ego. I have made investing mistakes in the past and I am quite sure I will make them again in the future.

But all this while, at least I have learned that in investing, playing the status game can be expensive.

The skills that lead to admiration in conversations are not the same skills that lead to wealth accumulation over decades in the market.

So instead of focusing on the fleeting admiration I get on my dinner table, I’d like to remind myself to focus on the actual improvements to processes that would contribute to long term profitability.

Cheers.

Ooops

Before you go off for real. I want to hear from you. What do you think are the behaviours you commonly see at your dinner table, friend gathering, etc that potentially displays a person’s investment underperformance or superb performance?

I have a couple of ideas for the superb performance ones. People who are really really good at investing also exhibit a certain behavioural pattern that you could identify. Let me know your thoughts in the comments.